R.I.P. Background Features

The most underrated mechanic in D&D 5e

Play any indie TTRPG worth its salt and you'll quickly learn that D&D 5e puts a lot of unnecessary strain on its DMs. Many other games have mechanics that aid the players in telling a specific kind of story: Some help the GM by giving them advice or procedures to follow, while others allow the players to act upon the world in meaningful ways and create their own plot hooks, sharing the creative load between the players.

For example, in Wanderhome, NPCs, locations and events all have lists of things that they can do. An NPC with the Learned trait can “Know something useful that applies to the situation;” a place with the Swamp nature can “Show tension caused by stagnation;” and during the Day of Song holiday, anyone can “Get a token whenever you take some time to listen to the music and describe how it makes you feel.” While these actions are certainly not exclusive to any one person, place or event, you can easily refer back to these actions whenever you don’t know what might happen next.

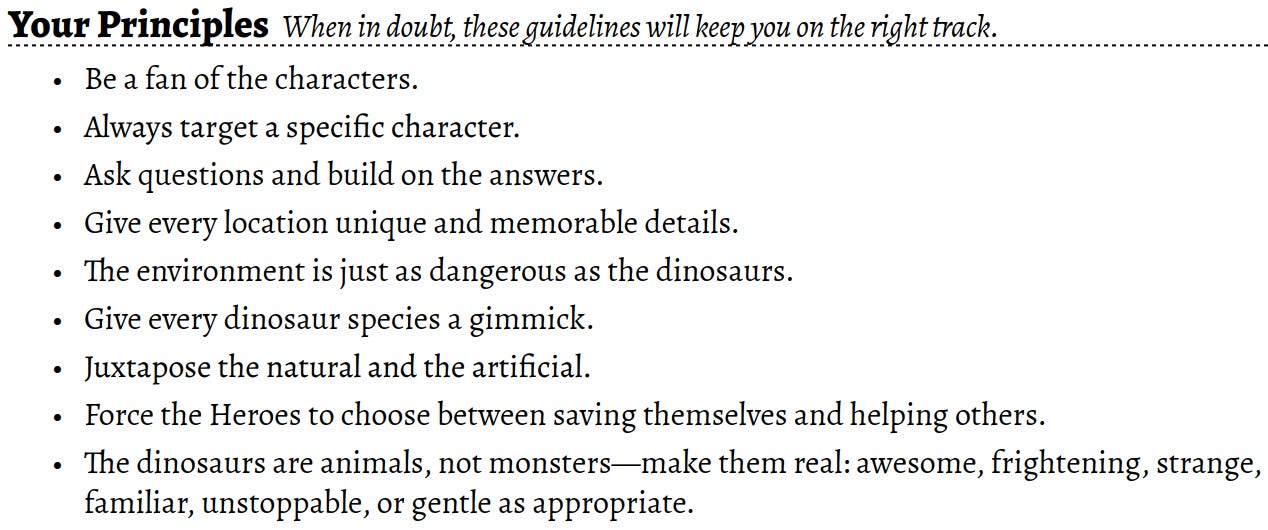

Other games, like those Powered by the Apocalypse, give the GM a list of principles that can help guide their storytelling. These principles generally reinforce the tropes of whatever story the game was made to tell. In Escape from Dino Island (a big homage to Jurassic Park), the DM (Dino Master) has the following principles:

This list is a mix of general good GMing principles (like “give every location unique and memorable details”) and advice specifically for the genre (like “the dinosaurs are animals, not monsters”). By keeping it all in mind, the DM can hopefully guide a story that’s more engaging, thematic and satisfying to play through.

Additionally, both games give narrative-focused abilities to the PCs. In Wanderhome, the Fool can ask “What’s going on?” and whoever helps them gains a token. This encourages the Fool to be clueless, fulfilling their role in the story. In Dino Island, the Paleontologist is the only character who can roll to see if they know anything about the dinosaur they’re currently facing, this allows them to flex their skills as a dino expert.

Mechanics like these take the weight off the GM’s shoulders by giving them guidelines for how to tell improvised stories, or letting the players guide the story themselves, splitting the mental load of improv between them and the GM.

D&D 5e is noticeably lacking in these mechanics. There is very little mechanical framework for any actions outside of combat. Non-combat actions are generally resolved with a single skill check of the DMs choice, and some classes, like many fighters, don’t have any ways to mechanically engage with the game outside of combat. While Xanathar's Guide to Everything later introduced more developed downtime mechanics (featuring random event tables!), I've rarely seen them used. You could also argue that Inspiration is designed to incentivise specific roleplay, but I don't think anyone has a coherent idea of when to give out Inspiration, so no one knows what they're actually being incentivised to do.

But there is one mechanic that every character has access to that drives the narrative like nothing else. It lets players show off unique skills or invites them to create NPCs, locations and even entire factions: the background feature. Every background in the 5e Player’s Handbook has a feature that is entirely narrative focused and has no effect in combat. For example, if you are a Folk Hero, you can freely find lodgings with common people, and they will even shield you from the law or anyone searching for you; if you are a Noble, your wealth and authority mean that “people assume you have the right to be wherever you are”, very useful for infiltration; and, my personal favourite, if you are a Sage, when you fail to recall a piece of information, you instead learn where that information can be found, which gives your character a sense of expertise and creates new plot hooks as the party journey to visit this new location.

I love these features, and I don’t think anyone gives them enough credit for how they can help the DM. Some of them come with implied NPCs (such as the Criminal’s contact and the Guild Artisan’s guild), or allow you to show off your skills, completely bypassing certain skill checks (like the Outlander’s foraging skills, or the Entertainer’s ability to perform for free room and board), but all of them encourage players to make narrative decisions that drive the story in some way.

So you can imagine my surprise when I learned they would not be returning in D&D 2024 (I'm still not sure what they want people to be calling this edition?), instead being replaced by feats, a separate mechanic which tends to be much more combat-focused. It's such a shame to take out this mechanic, since it was the main player-facing story driver in the core three books. There's nothing that really fills the same gap as background features, they're not powerful enough to be class features or feats, so I suppose they'll just fall to the wayside.

But this was not a sudden shift, the design of backgrounds slowly changed over the course of 5e’s lifetime, leaving many of the backgrounds from the Player's Handbook mechanically inferior to their successors, and leaving me confused as to what backgrounds are trying to achieve in this game at all. Let's take a look at the evolution of background features over D&D 5e’s lifetime and see what happened to the most underrated mechanic in this game.

The shift began in 2018’s Guildmaster’s Guide to Ravnica, the first of many Magic: the Gathering settings to receive 5e sourcebooks. The book contains 10 backgrounds, one for each of the world’s guilds. Each Ravnica background comes with an expanded list of spells that any spellcaster with the background can learn, even if it isn’t normally on their class’ spell list. For example, a wizard in the druidic Selesnya Conclave has access to spells like Druidcraft and Commune With Nature, while a cleric in the demonic Cult of Rakdos could prepare Hellish Rebuke and Enthrall.

I actually really love these! The expanded spells are given in addition to a more standard background feature, and since nearly everyone in Ravnica is a member of one of the guilds. So, while they may be a little more powerful, these backgrounds are supposed to be used instead of the ones in the Player's Handbook, rather than alongside them.

In a similar vein, 2021’s Strixhaven: A Curriculum of Chaos features 5 backgrounds for the 5 colleges that make up the titular magical university. Each Strixhaven background gives you an expanded spell list as well as the Strixhaven Initiate feat instead of a classic background feature. Strixhaven Initiate gives you access to 2 extra cantrips and 1 extra 1st-level spell based on the college you’re studying at. Like with Ravnica, these backgrounds are intended to be used instead of Player’s Handbook ones, so the difference in power is unlikely to come up in play. But this marks the beginning of a power shift that leaves the Player’s Handbook backgrounds firmly in the dust.

Up until this point, other books like The Wild Beyond the Witchlight and Van Richten’s Guide to Ravenloft contained backgrounds with features similar to those in the Player’s Handbook: being a Feylost makes Fey creatures friendly to you, and being an Investigator means you can freely access any location related to your current investigations. This is the last time that backgrounds in mainline 5e books had features with this design principle.

In 2022, The Astral Adventurer’s Guide was released. Its 2 backgrounds (Astral Drifter and Wildspacer) both grant you feats from the Player’s Handbook: Tough and Magic Initiate respectively. This is a dramatic shift in the background design principle, the narrative features are nowhere to be seen, instead replaced by feats that are generally considered to be pretty powerful. This style of background continued to be used for each mainline release afterwards, sometimes offering you feats from the Player’s Handbook (like in the Book of Many Things), and other times offering you new feats from the new book (like in the Dragonlance and Sigil sourcebooks). Each of these books only contains 2 backgrounds, so there aren’t even enough to give to a full party of 4 without doubling up, and I can’t imagine you’re expected to use the Spelljammer backgrounds alongside the Dragonlance backgrounds, alongside the Sigil backgrounds, without touching any of the Player’s Handbook ones.

This noticeable difference in power level makes the older backgrounds completely unappealing to players. Why would you want to be good at foraging when you can have extra HP? Why would you want to be able to sleep in a church when you could cast cure wounds an extra time per day?

By taking out mechanics like these, D&D continues to make itself more difficult to run. It doesn't surprise me that the D&D community constantly has to deal with a DM shortage, when putting in the work to run this game feels more and more like something you should only be doing if you're paid to. I genuinely hope that the new Dungeon Master’s Guide is an actually useful tool for DMs, since right now it seems like DM support is only getting worse and worse. But there are already plenty of indie games that have amazing, official GM resources that can help you run the game in a way that makes it sing, like the two I mentioned back at the beginning! I promise, they're not as hard to learn as you think, and you'll probably have an easier time running them than D&D 5e.

posts that make me wanna play wanderhome (and also never run a dnd campaign in my life /exag)